In which the Wilcox brothers write home while their brother, my G-G-G-Grandfather stayed home and tended the farm.

Vicksburg, March 13, 1863

Most of the regiments have moved up on the levee, and we have drawn our guns up. Half a mile below us the country is flooded.

Camp near Vicksburg, March 28, 1863

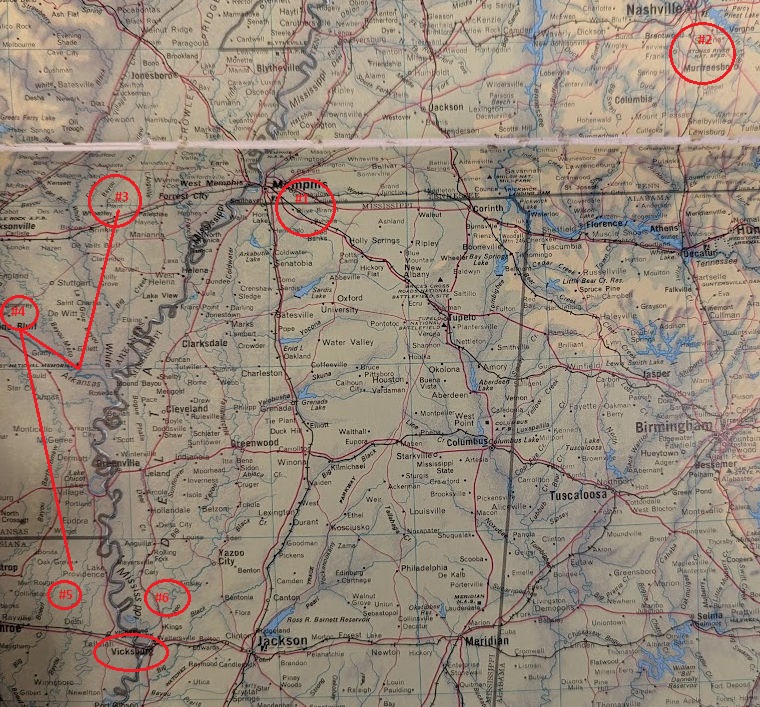

We arrived in camp last night after dark. We started on the 20th from here with one section of our battery. Thomas and I went on the YazooRiver about ten miles, then turned into Steele Bayou, on the left side of the river as you go up the bank. We went about 60 miles from the Yazoo. We were landed to guard the bayou, to keep them from felling timber into it. We camped on the first dry ground we came to on the Black Bayou. We enjoyed the time we were in camp very well, sailing in the canoes we found along the bayou.We came back on the gunboat Louisville. About 200 negroes, women and children, came back with us. The whole thing was one complete failure. The infantry had to wade in water up to their knees.

Willard Wilcox

~

Camp before Vicksburg, March 29, 1863

Willard and I have returned from an expedition up the Yazoo river. It was a failure. The order came about 10:00 at night. Of the 19th, for the two howitzers. We went over 60 miles. Came back on gunboat. We were on a plantation.

Thos. Wilcox

April 5, 1863

Thomas ill: “I have stayed in camp, and the boys have taken first rate care of me.”

~

Milliken’s Bend, May 3, 1863

Wilber was up in the Chickasaw and fought the battery for three hours without being disabled, but was struck a great many times.

Rear of Vicksburg, May 5, 1863

Have to stay at the guns most all the time. We were called up every night to fire ten or fifteen shots. The squads take turns of two hours each in firing it, or 25 shots at a time. Our men are getting all the heavy guns mounted and rifle pits dug to within 100 yards of the rebel works. Every battery on the line opened up on them one morning about 3:00 o’clock; for hours it seemed like a stream of fire from one end of the line to the other. One thing is certain, they cannot stand it much longer. We keep getting closer every night, and will dig them out. I would like to come home when we take Vicksburg. It seems a long time since I went away. Willard is as strong as ever. The Captain said that he is the only one that stays at the cassion that he can depend on to get anything done when he wants it. I do not like soldiering, no way you can fix it.

Thomas Wilcox

~

Milliken’s Bend, La. 25 miles from Vicksburg. May 7, 1863

Willard has got over his fever. I am about well. The boys came back from their expedition without firing a gun. They went up the Yazoo River to Haines’ Bluff. The troops have all gone below Vicksburg except our division. We have a nice camp. We left Milliken’s Bend May 6, and went to Grand Gulf, and started for the bridge across the Black River. Water was scarce, and the roads so dusty we could not see two rods, and we were on half rations, but we stoof it first rate. We were in position three times but did not fire; were under fire several times. General Sherman ordered our battery up to the river bank, but after five shots they hoisted the white flag. Squad 2 crossed the pontoon bridge first with six horses.

Near Vicksburg, May 30, 1863

Left Young’s Point day before yesterday to join the company. Went up the Yazoo about 12 miles. We landed, found the battery near the place on the opposite side of the Chickasaw bayou from where we were last fall, near the place where 6th Mo., undertook to cross. Wilber and Thomas are here.

W. J. Wilcox

~

We have been under fire for six days, within 400 yards of the breastworks. The four gun squads have to stay at the guns night and day.

Rear of Vicksburg, May 30, 1863

Thomas and Wilber are looking well. Our line of battle is on one range of hills, theirs on another, being about 400 yards apart. Where our battery is, we have got our line intrenched, but skirmishers keep firint at one another when they see anyone. Ore battery fires more or less every day. They brought in four 30-pound Parrotts last night. Our boys have one to man. They have to keep it going all the time, so they take turns at it. They fire all over, sometimes clear in to the center of town.

Willard Wilcox

Near Vicksburg, May 31, 1863

The most trouble is to stand the heat. We are on the side of a high ridge without any shade, and in the middle of the day it is very hot, especially if we shoot. Yesterday we got up a 30-pound Parrott gun and fired 100 shots from it, and at 6:00 A.M. we fired from one end of the line to the other. They have got so that they don’t fire back but very little.

Camp in rear of Vicksburg, June 4, 1863

Our lines have not advanced since I came here excepting in places where they are making approaches which I don’t know much about. Both parties lie behind their works occasionally exchanging shots with small arms. We have fired a great deal with the artillery. You can form some idea of the amount, as the gun that I belong to fired 633 shots. If the Eastern armies could gain a victory, it would be a better feeling.

Willard Wilcox

~

Camp in rear of Vicksburg. June 16, 1863

Vicksburg is not yet taken, but Grant and Sherman are working as fast as the rough nature of the ground will permit. The amount of work done by the army since we have been here is almost past belief, yet the men work with a good will, confident that we will have Vicksburg in spite of Johnston. There is not a day passes, but more or less men are killed.

Wilber Wilcox

~

Camp near Vicksburg, June 23, 1863

We have a new battery, five light 12-pounders and one 10-pound Parrott gun. They will carry farther than our old battery; our men are at work making approaches. They are within a few feet of the enemy’s ditch in several spaces, but there has got to be a parallel ditch dug to hold many men before they can storm it. Our pickets are in one ditch while theirs are in another. They used to talk a great deal, but that has been forbidden, so they write on pieces of paper and pass backward and forward. One of our boys threw over a part of a loaf of bread and they threw back a biscuit. You can talk to them quite easy from the guns where Thomas stays, when they are on the breastworks.

Willard Wilcox

The siege ended on the 4th of July, 1863. The brothers would then march to the sea with Sherman, Eventually, one of them would die and only the two would make it back home (John having already died at Chickamagua).

A “Parrott” gun was a cannon.

If you want to learn more about the Battle of Vicksburg, the following are some links to get you started.

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/maps/vicksburg-campaign-1863

https://www.battlefields.org/visit/virtual-tours/vicksburg-virtual-tour