My dad sent me not only dry Family Tree diagrams, but a few photos and several vignettes of history.

Sarah Lord Wilcox takes up quite a bit of space in the vignettes, in stories that are not just about her, but are about her sons and the Civil War. I am guessing that my Uncle Mike typed the stories out and that he has the original letters the story teller refers to. I hope so. I want to know someone in the family owns the originals. (This means, of course, that a letter to Uncle Mike is in order)

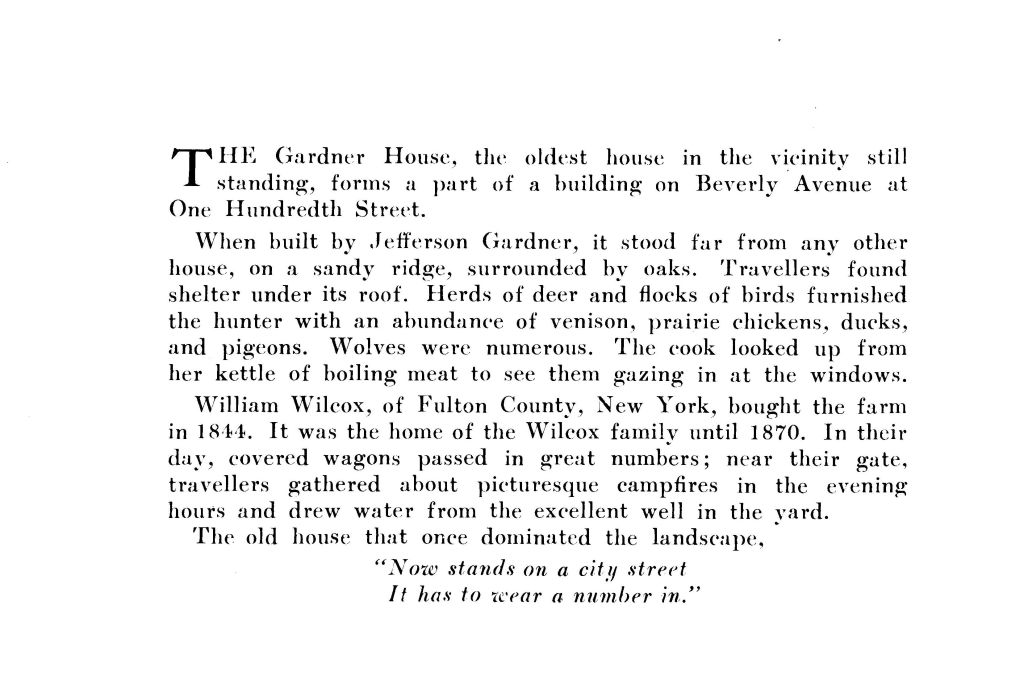

Sarah Lord married William Wilcox the year they both turned 28. that was old for a bride in those days and way past traditional childbearing age, but she went on to bear seven children to William before his death. Sarah and William lived in Johnstown, Fulton Co., New York until 1844 when they moved to Illinois, somewhere near Chicago. William died within a year of that move, leaving Sarah and her seven children. She took in boarders, but she was really known for her skill as a weaver.

In 1861, the war began. Four of Sarah’s sons enlisted: Wilbur, Willard, Thomas and John. Reading the compiled history of the war: Shiloh, Corinth, Tallahatchie March, Stone River (Murfreysbury), Chickasaw Bluffs, Vicksburg, Jackson…

From one of Willard’s letters:

“Our men are at work making approaches. They are within a few feet of the enemy’s ditch in several spaces, but there has got to be a parallel ditch dug to hold many men before they can storm it. Our pickets are in one ditch while theirs are in another. They used to talk a great deal, but that has been forbidden, so they write on pieces of paper and pass backward and forward. One of our boys threw over a part of a loaf of bread and they threw back a biscuit. You can talk to them quite easy from the guns where Thomas stays, when they are on their breastworks. -Willard Wilcox.”

“Our pickets” are the Union soldiers and “theirs” are the Confederate soldiers.

At the Battle of Chickasaw, in September of 1863, the Union army took a beating. Out of that rout came a letter from Sarah’s son-in-law, D.E. Barnard. (I may be a bit confused on the relationship – one of the Barnards was a son-in-law, two of them were in service with the Wilcox brothers.)

“I write to you now after the sad events of the last few weeks, not to inform you of John Wilcox’s death, but to give some of the particulars so far as I am able. Saturday morning we marched to the battlefield in haste, to the sound of the cannon… Sunday morning we drew rations; the 36th not getting theirs, we divided with them. John was very active in this, giving freely of his rations. When we went into battle he was by me and in the first line. He was fighting among the foremost. Soon, although we had driven the rebs (sic) immediately in front, they were gathering along both flanks on our left. Only a little in front I saw a rebel flag of a regiment, and called attention to it. We were directed to fire oblicuily (sic) at them, which we did, but as the fire grew hotter on both flanks, we were ordered to fall back, which we did, and rallied at the foot of the hill. During all this time John was with me. Soon I noticed that he stooped down. I asked him if he was hurt. He said he was hit in the foot with a spent ball. I asked him is he had not better retire, and if he was disabled.he said no, and kept on firing. Soon we fell back again by order, and he with the rest. I looked carefully but did not notice any particular lameness or blood. At this time I was among the last retreating, and a man badly wounded in the leg, a stranger, asked to be helped off the field. This I could not do, but just then one came with a wounded horse which he was leading, and offered to carry him on the wounded horse if he could get into the saddle. No one else offering, I helped him on, and he rode off rapidly. This left me in the rear, and I found the balls thick around me. I hastened to join the regiment. When I reached it, at some distance from the place, I found several absent, John among them. I inquired for him, and was told that he had been again wounded in the leg, and that he was making to the rear, and had doubtless got on a wagon or ambulance. As I could not find him, and I looked for him, I supposed this to be the truth, but at this very time he was probably dead, shot through the left breast. He must have died instantly. Such is the report of Sergeant Strouch who knew him well, and who placed his body under a tree, covered it with his shelter tent, and placed his head upon a knapsack.” — letter dated October 9, 1863.

John’s body was never recovered and he was buried as an unknown soldier among the many who fell in battle that day.

What a tear-jerker! And what a history: going from the one moment when enemies tossed bread & biscuits back and forth, to fallen heroes on both sides of the lines. There’s a lot more, but I wanted to share those most poignant letters.

Sarah Lord Wilcox lived to be almost 86. She was born 18 October 1797 and died 2 October 1883. She married only the one time.

Read Full Post »